Archie Hum

An Interview with Archie Hum

Many years ago my father and several brothers came over from Taishan in Guangdong Province, China, to this country. They operated a Chinese restaurant, Port Arthur, on 6th and Hennepin in downtown. Subsequently my father was able to get his wife to join him here, despite the government?s ban on Chinese women from entering this country. They had more children here and I was one of the ones born here. All together there were 8 of us: 6 boys and 2 girls. We lived for a while in St. Paul and then moved to Minneapolis at 226 S. 8th Street. There were several other Chinese families living in the building at this address, including Oy Huie Anderson?s family. The family of Jimmy Hong, the legendary Hollywood actor, also lived there. Jimmy and I grew up together. We played with all the families on the street, including Caucasians and Native Americans.

Many years ago my father and several brothers came over from Taishan in Guangdong Province, China, to this country. They operated a Chinese restaurant, Port Arthur, on 6th and Hennepin in downtown. Subsequently my father was able to get his wife to join him here, despite the government?s ban on Chinese women from entering this country. They had more children here and I was one of the ones born here. All together there were 8 of us: 6 boys and 2 girls. We lived for a while in St. Paul and then moved to Minneapolis at 226 S. 8th Street. There were several other Chinese families living in the building at this address, including Oy Huie Anderson?s family. The family of Jimmy Hong, the legendary Hollywood actor, also lived there. Jimmy and I grew up together. We played with all the families on the street, including Caucasians and Native Americans.

Later on we moved to a building on 3rd Ave. It was sort of a commercial area, with many more apartments. My father started a laundry service after they closed the restaurant. In 1934 when I was 9 years old and in third grade my parents decided to take the family back to China because they were concerned that we were growing up to be Americans, and they wanted us to experience some Chinese culture. So they entrusted the laundry to a friend and took 7 of us (my oldest sister did not go) back to Taishan by way of Seattle and Hong Kong.

During their 20-some years in Minneapolis my parents had been sending money home to have a house built. So when we arrived we had a house waiting for us. However, there were no utilities in the house. There were no toilets, water or stove. We had to go to the river to fetch water and not knowing anything about sanitation we would drink the water right out of the river. That was not a good idea!

I could speak very little of our village dialect when we arrived, but I could tell when the local boys were calling me names. So we got into many fights. It took a couple of years before I learned the dialect well enough to communicate. In time I developed some friendships. Overall it was a huge adjustment.

After a couple of years my father left to come back to Minneapolis, and my oldest brother, Albert, left for Sumatra; but my mother and the rest of us stayed in our village. My mother had saved up a lot of gold and silver that she kept in her strong box. I assume that was what we were living on. I went to school through 6th grade and shortly after I started junior high school the teacher flunked me because I acted like I knew more English than he did. So I quit school and just roamed around. I went to Guangzhou often, but when the Japanese planes started bombing the city I quit going. Our village was only 5-10 miles from Guangzhou and we could hear all the bombs. Fortunately our village did not experience any bombing while we were there.

When I was 16 (1941) Albert came back for a visit and asked if any of us would like to come back to Minneapolis with him. I jumped at the chance.

In Hong Kong Albert and I boarded a Japanese passenger ship bound for San Francisco. It would turn out be the last Japanese ship to arrive in the U.S. before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. When our ship arrived in San Francisco, for some reason we did not dock. The captain probably had gotten an order from someone in Japan to keep circling San Francisco Bay. Finally he was forced to let all of us (mostly Chinese passengers) off. Albert and I had our passports and birth certificates and were able to pass through Immigration easily.

When we came back to Minneapolis, another brother, Fred, was already here. He had left our village some time before me to go to Sumatra to help with the business of an uncle. From there he had made his way back to Minneapolis.

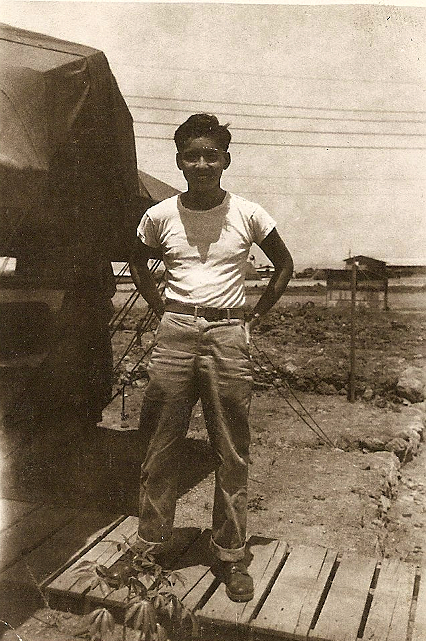

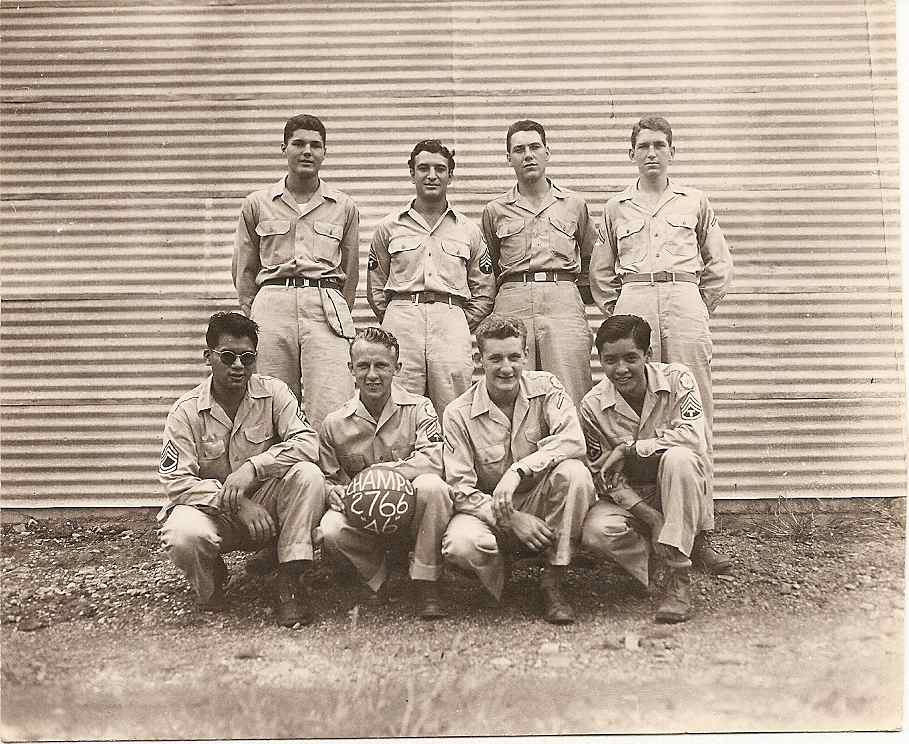

So it came about that three of us boys, Albert, Fred and I were here when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. I remember hearing the news on the radio. Within the next two years, all three of us enlisted.

bombed Pearl Harbor. I remember hearing the news on the radio. Within the next two years, all three of us enlisted.

Before enlisting I resumed school in Minneapolis and attended Marshall High School. We were living on East Hennepin at the time. During the first year at Marshall, I was placed into 10th grade and mostly kept my mouth shut in class. At the end of the year since I knew English they let me pass and on to 11th grade the next year.

I was the only Chinese in the school and got into a good number of fights because of it. I did not like being called ‘chinky chinaman’ and would get my first punch in first. I did not want to hurt anyone, but if someone forced me into it I would fight. I would not stand there and let someone kick me. In time we became friends. The girls all liked me because I was polite to them.

I settled into a routine of going to school at Marshall in the daytime and working at the laundry at night. Sometimes I would sneak off after school and go to work somewhere else, like at a western-style bakery, for a couple of hours. I could make 75c/hour there and this pay became my spending money. $1.50 went a long ways back then. No one knew I did that!

After I graduate from Marshall I was called up to serve in the Army. The doctor who examined me asked if I could dig a hole. I asked how deep and he said deep enough to bury myself in. I answered no and received the grade of 4F: unfit for service.

Next year I was called up again and this time when the doctor asked me the same question again I answered yes! I was admitted. It was by then 1944.

After basic training I was sent to the Philippines on a troop ship. Everyone got sick on this particular liberty ship because it was too small.

After basic training I was sent to the Philippines on a troop ship. Everyone got sick on this particular liberty ship because it was too small.

I was the only Asian in the infantry in Manila training for the invasion of Japan when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Those bombs saved the lives of a lot of GIs. Had it not been for those bombs, I might not be sitting here right now. We traded places with the Japanese people and were given a second chance to live.

During my time in the Army I did not know how to communicate with anyone in my family. Everyone was scattered and I only knew for sure that my father was in Minneapolis. But he could not read English and I did not know how to write in Chinese, and depending on where I was, there was not always reliable mail service. Still, I wrote my father something to let him know that I was alive. My mother was still in China and there was no way to communicate with her. Every time at mail call, everyone would rush over waiting for letters from home, but I never went because I knew there would not be anything for me.

In a way receiving letters from overseas would be like reminding me of a different life altogether. I never cared that I did not get any letters from home because I knew I might die anyway. We were preparing to invade Japan and I did not want to act like a coward, even though I felt like one inside. I just hoped that I would be lucky. I was not a believer in any religion at the time, but I felt that praying for myself to be lucky was really like praying for the other guy to be unlucky.

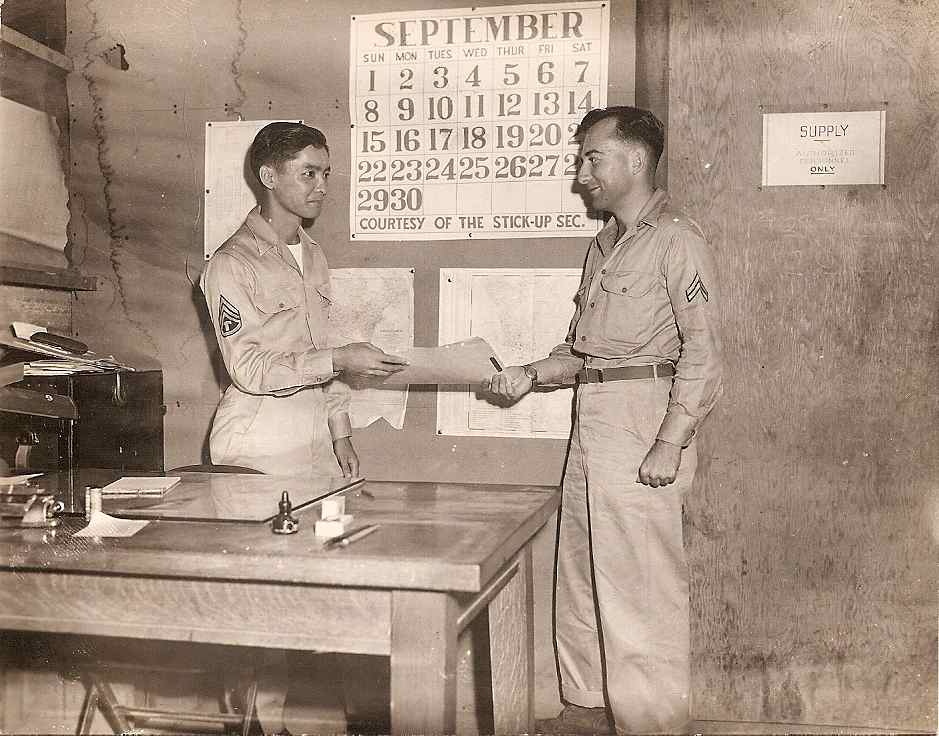

These feelings changed when the War was over. While I still had to stay in the Army to serve out my tour of duty, things felt more like status quo rather than looming death. I went into the topographic division and ended up making maps from aerial photographs in an air-conditioned office. I stayed on in the Philippines for two more years.

out my tour of duty, things felt more like status quo rather than looming death. I went into the topographic division and ended up making maps from aerial photographs in an air-conditioned office. I stayed on in the Philippines for two more years.

There were then only one other Chinese besides me in my division. He was the surveyor, and I ended up being the first sergeant in charge. So everyone had to nice to me.

My oldest brother, Albert, enlisted for the Air Force and was trained as a bombardier and stationed in China. Together with a pilot and a navigator, he was flying B29s in bombing missions to Japan. There was no sense for me to ask him questions. He was an officer in the Air Force and I was in the Army. It was like we were in two different organizations.

My other brother, Fred, was serving in the Army in North Africa. He kept up a correspondence with Oy?s older sister. Oy says he once wrote her sister a letter on toilet paper, explaining that was all the paper he could find. This may or may not have been true: all of us were hopeless jokesters.

Throughout the War the three of us were each busy doing our own thing, and did not ask each other about what the others were doing. At the end of the War, we were surprised to find that all three of us were alive.

One of our childhood playmates and neighbors was Phil Huie, Oy?s brother. Tall and affable, Phil was often at the receiving end of our practical jokes. He was also drafted and spent his tour as a cook in the Philippines. This was in accordance to the Army?s unwritten practice: Chinese were cooks, Filipinos were waiters, and African Americans were drivers. It did not matter that Phil had never spent a day in his life in the kitchen.

The most memorable thing about my service in the Army was that I came out alive. I was the luckiest guy in the world. 50,000 Americans gave their lives, but I was given a second chance to live.

After my discharge I decided to attend the University of Minnesota on the GI Bill. I think this Bill was fair: it offered us something for having put our lives on the line for our country. There were many veterans in my classes. We were all trying to do the same thing and none of us was selfish or felt competitive. We all wanted the same thing and were willing to help each other out to achieve it. Whatever else we were, we were buddies first. If someone needed a lot of help, we were all there to lend a hand. There was an unspoken brotherhood. We all survived. That made a difference.

The GI Bill paid for my tuition and textbooks, plus a $15/month stipend for living expenses. To make ends meet I would work on any job that would pay: sweeping the streets or anything I could find in Minneapolis. At first I did not have a car, later on I got what we called a ?jalopy? and found that then I had to work extra to pay for gasoline!

Some time after the War my mother came back with my other four siblings: sister Lillian and three brothers. They were lucky to have survived the Japanese occupation in China. I frankly had not expected to see them again.

My mother told me that whenever the Japanese Army got close to their village they would all flee to the countryside to hide. One of her cousins had gone to college in Japan (a popular custom at the time) and graduated from the University of Tokyo before the War. He spoke fluent Japanese and once when the Japanese Army came to their village hewent up to them, hoping to talk to them in Japanese in a reasonable way. Instead a Japanese soldier pushed a rifle into his mouth and shot him dead. Our U.S. military would not have tolerated such a lack of discipline. A U.S. soldier doing that would have gotten hung. Sure we were trained to kill, but only other soldiers, never an unarmed civilian.

Anyway, after everyone in the family returned to Minneapolis we rented an apartment for all the siblings while my father and mother lived at the laundry on East Hennepin. We would all go back there for dinner.

I graduated from the University with a degree in mechanical engineering and went to work for an architect, Ellerbe Architects, for 40 years. I worked on air conditioning and other facilities in buildings, especially hospitals, including the Mayo Clinic. We became known for our expertise nationally and I traveled a good bit around the country.

I was not active in the Chinese American Club in Minneapolis after I graduated. I was too busy having fun dating girls, including Caucasians. They were willing to date me, but we all knew that they would not be marrying me. I did not care anyway. And interestingly, I met my wife, Velma, through one of them. Velma was living in a dorm in St. Cloud then. We got married and built this house together. We have one daughter, Missy. Now Velma is gone and I live alone here.

Anyone who has gone through a war recognizes certain facts of life. There will always be war. If you don?t stick your nose in, someone else will. Human beings are just that way. In my years of attending the Chinese Sunday School at Westminster Presbyterian Church I learned that Christianity is very much about helping others, to the point of sacrificing oneself. Our Chinese philosophy is little different. Where I came from, we were all so desperately poor that all we could do was try to take care of our own, and not to harm anyone in the process.

In closing, I wish to say, ‘God Bless America.’ I feel that I am already in heaven. Let us all work to make this goal happen: U.S.A. is heaven. If this country needs me again, this 87-year-old will be in line to help.